Breeding

Breeding snails in captivity is not an exact science to say the least and at the moment has a lot more to do with luck than anything an owner can control. Understanding the process can only be a good thing, so this part of the care guide will attempt to shed some light on snail breeding from mating to egg rearing, including other issues that may be of importance to someone interested in breeding snails.

The Mating Process

Mating Ritual

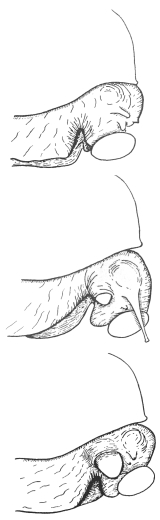

When preparing to mate, snails often go through what may be described as a mating ritual which can involve playful biting and rearing up to one another. One of the most distinct examples of this is Helix pomatia, which rear up as if they are fighting and act as though they are kissing. This can go on for a number of hours. More often than not it is one stimulated snail trying to get another interested and it is not uncommon to see one snail wandering around with its penis hanging out of the genital aperture looking for another snail who is interested in mating.

"We have not yet observed the whole sequence of events in the mating behaviour of Archachatina. Pre-copulatory exploration of one snail by another and excitement (swelling of genital papilla and rapid dorsal body waves) have frequently been observed, normally subsiding when the prospective partner shows no response." 1

Copulation

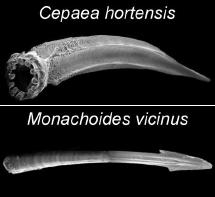

Some species actually inject a calcified dart into the other snail to stimulate copulation. This "love" dart has been shown to actually increase the chance of success by effectively injecting a chemical which retards the sperm-resisting abilities of the receiving female reproductive organ. It has no doubt evolved as part of a sexual arms race. You may see this occurring but it's nothing to worry about. You may also find the darts themselves.

"In a paper that caught the attention of the popular press, Rogers and Chase (McGill University, Montreal) report that a component in the mucus coating the love dart of Helix closes off the partners copulatory bursa which digests foreign sperm, and as a result darted snails retain more of the partners sperm (Behav. Ecol. & Sociobiol. 50, 122-127)." 2

Mating can last from a few minutes to possibly many hours, with owners awaking to them still mating. Whether this is the same coupling or a subsequent one has yet to be determined, though the former is more likely.

"Although the act of intromission has not been seen, snails have been found in coitus. The following description applies to two animals found in this condition one morning. The heads and cervical regions of both snails were much distended, the thick penes (5-8 mm. diameter) having a heavily papillated appearance... Both penes curved round the head of the supine snail to the head of the dorsal snail, the exposed portions being 5-6 cm. in length. Each penis made one slow turn round the other, entering it's partner's genital aperture posterior to the emergent penis. Slow peristaltic waves passed outwards along each penis. A mass of greenish jelly surrounded each genital aperture, extending some distance along each penis, and both snails were busily ingesting this material.

After about 10 minutes the penis of the upper snail (S2) was retracted from the genital aperture of the [lower snail] S1, followed about one minute later by that of S1. The action was a slow pulling apart, followed by a sudden emergence. At this stage the apparent terminal part of the penis was broad and papillated. Each penis was estimated to have had an extended length of 12-14 cm.

Mead (1950) after describing populations of Achatina fulica, stated that he inspected the vas deferens of one of them, finding several white sperm masses but no evidence of spermatophore formation. On the other hand, twice when dissecting fresh Archachatina, we found a structure in the large hermaphrodite duct that we are compelled to suppose was a spermatophore." 1.

|

A. immaculata

Mating Sequence |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| Click pictures above to see large versions. Pictures courtesy of Sarah Fowler | ||||

Gestation & Laying

Eggs visible from the pneumostome. Picture courtesy of ????

Eggs visible from the pneumostome. Picture courtesy of ????

Snail eggs can be hard-shelled or quite soft and squidgy and differs from genus to genus. In either case, the eggs resemble tiny chicken eggs in shape but contain no yolk.

Snails often hold the eggs inside a special membrane, visible through their pneumostome as shown opposite. In ideal circumstances they don't hold them for very long, laying them when they consider the environmental conditions to be suitable. It is worth noting that it is this ability to retain the eggs that is likely to be responsible for the 24-48 hour hatching times we sometimes experience. It is not that they use any body heat to incubate them, rather they have escaped notice of the owner and so appear to have an abnormally short development time.

Some species like Achatina iredalei actually retain eggs until they are fully hatched. This is known as viviparity and snails that do this are called viviparous as oppose to ovoviviparous which is the egg-laying norm. It has been observed that baby snails born of this method sometimes have slightly dented shells, no doubt caused by the stress of birth.

Archachatina marginata laying eggs.

Archachatina marginata laying eggs.

Some species, such as Achatina zebra actually have the ability to do both, so they can still produce eggs when environmental conditions aren't quite right.

Snails usually form an egg chamber in the soil and then proceed to fill the chamber with eggs. This can sometimes be completed throughout the course of a few nights, with one night dedicated to creating the chamber, with the laying commencing the following night.

"Snails about to form an egg chamber tend to enter the soil with the left side of the shell adjacent to, and the head and foot parallel to, the wall of the vivarium. Thus, since the shell sits eccentrically on the body of the animal, the columellar axis of the shell has an angle of approximately 15° to the wall. With the head retracted the snail forces the lip of the shell into the soil, raising an arc-like mound of thelatter over the body whorl as it penetrates more deeply, the shell thus behaving rather as a plough-share. The depth of the burrow varies with the size of the snail. As a rule it may be 4-6 inches below the surface at the shell lip, the soil at this stage normally covering the shell. The snail constructs a smooth-walled chamber of oval outline that is usually no more than ½ inch from the wall of the vivarium and deposits its eggs in a group only the peripheral members of which are in contact with the soil.

The rate of oviposition can be quite high. It has been observed to completion several times in snails apparently compelled to lay their eggs on the surface. In these conditions it may take from 30 minutes to 2 hours. One snail was observed to lay 6 eggs in 30 minutes. The time from the appearance of the egg in the genital aperture to the final extrusion was approximately 1 minute: 4 minutes later the next egg appeared. The last egg was slower to appear, the total time between its extrusion and that of the penultimate egg being 8 minutes. The head of the snail just protruded from its shell, there was a period of small movements, with contraction waves over the head and with tentacles extending and invaginating. Then the right posterior and anterior tentacles were extended, a bulge in the head grew larger, the genital aperture gaped below and behind the buccal bulge (apparently the buccal mass) and the tip of the egg appeared. The latter was now seen to be causing a more posterior swelling of the head beneath the shell. The was a pause of about 30 seconds, the egg was then forced from the genital aperture which shrank behind it and, simultaneously, the right tentacles were swiftly invaginated." 1.

Hatching & Early Life

Achatina achatina hatching

Achatina achatina hatchingPicture Courtesy of Liselott Aronsson

Lignus intertinctus hatching

Lignus intertinctus hatchingPicture Courtesy of Lorna Mae Wyatt

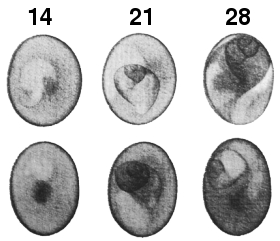

The eggs will start to hatch from 24 hours onwards in some species but it is genus and possibly species dependent, with additional factors of how long they have been stored internally and the ambient and soil temperature. Eggs do not necessarily hatch uniformly and this is more noticeable in species that have a long gestation period (perhaps 4 weeks). The first (usually an uppermost member) to hatch can be 10 days or more in front of the main group, with some taking noticeably longer.

"The late embryo, having ingested the albumen, continues to rasp at the egg shell, eroding this and weakening the wall. Occasionally a hole can be seen in the egg shell just before the occupant hatches. At this stage, pressure and movement by the embryo cause the egg to split. The embryo continues to rasp the shell, breaking it down and ingesting remarkably large pieces. Examination of the oesophagus of such a baby snail shows this to be distended by relatively huge pieces of shell. At this stage the early hatched animal is a danger to its siblings.

..The ingestion of the egg shell appears to be an important element in the development of the young snail and our records suggest that removal of the egg shell delays early growth. This may not be due only to the need for calcium carbonate because natural chalk us usually present in the propagators and vivaria."

Newly hatched babies often predate on the eggs around them, presumably this is a mechanism that ensure at least a few have a great start in life. It is reported that leaving the process to occur naturally results in a viability of 70% as opposed to the 100% viability if newly hatched snails are moved from the clutch. This is less of a problem in species with shorter hatching times because the eggs seem to hatch more uniformly.

Newly hatched snails will often stay burrowed for up to 14 days, presumably while they process and exist on the sustenance the shell provided. From this point on, young snails behave almost exactly like the larger ones they quickly grow into. There is no change to the physiology of any kind, new shell is appended to the shell lip and the shell grows spirally, and the body with it."1.

The shell whorls they are born with are known as the nepionic whorls and it is often the sculpture and other identifying marks on these that help malacologists determine their genus and sometimes species in later life, providing the haven't worn off as often occurs.

Captive Breeding

Early Considerations

The first thing you need to ask youself is if it is worth hatching babies. Species like Achatina fulica are so prevalent you will be hard pushed to find homes for them. If you do decide to hatch them, you need to try and work out how many. Hatching a full clutch is easier than saving some, because the eggs can remain largely undisturbed and it is hard to know the viability of the eggs and the young snails.

If you wish to hatch eggs only for the chance to see the process I would suggest obtaining some native snails so the young can be returned to the wild.

Encouraging Breeding

This is largely down to luck but there are certain things than can be done that may help. In the wild, largely dependent on climate and habitat, some tend to breed at any time of the year, others are more seasonal. This hints of a few things that could be a factor. For example, as taken from the Achatina achatina page:

According to Hodasi (1979), studies of Achatina achatina under laboratory conditions indicate that the species breeds from April to July, which coincides with the major rainy season and the longest days of the year. They are reportedly less abundant during this season than in the minor rainy season which occurs from September to November. This phenomenon could be a function of the complexity of the snails' reproductive ecology, growth characteristics and annual physiological rhythms.

It would seem then, that although the small rise in temperature and the minimal increase in day length no doubt play a part in determining seasonal changes, the biggest factor in triggering breeding is an increase in humidity. Eggs laid at the optimum time will hatch just in time for the major rainy season, giving the baby snails the best conditions for fast growth. It must be noted that the snails have less than 4 months to develop before the next dry season.

Similar information is noted in "Observations On The Reproduction, Growth And Longevity of a Laboratory Colony Of Archachatina (Calachatina) marginata (Swainson) SubSpecies Ovum by Jenifer Plummer" regarding the wet seasons of Nigeria.

If you are hoping to in some way influence this process, switching conditions from a dry, cooler, short day length environment to a wet, hot and longer day length may be a key factor, although for equatorial snails day length and temperature difference may be negligible since they are so steady throughout the year. There are some other factors as well:

It has been shown that overall the snail Helix aspersa breeds best when in larger groups with plenty of space. Too high a density of snails discourage breeding and it is remarked that large amounts of their slime may in fact be a prohibitive factor in these cases. This also tells us to keep the tanks clean of snail slime.

Similarly, not all snails will mate with each other, introducing new ones to a population can spark interest. It is also possible for one snail to encourage another so placing a sexually active snail with seemingly inactive ones may trigger a response.

Snails often withhold egg production if there is not a suitable environment for them to lay. Keeping your snails on deep, damp substrate will, if not actually encouraging snails to lay, will certainly not discourage it. Snail farms who keep snails on very little substrate actually place pots of substrate in the enclosure so the snails are forced to lay in them. Having said all of that, withholding substrate won't prevent eggs successfully so it is certainly not a reliable method of population or birth control.

Care of Eggs

Sometimes eggs will be laid on the surface of the soil but in most cases the snail will lay them deep in the soil.

So far, from what we have seen small eggs such as from European species and African Achatina species should be relatively easy to hatch. Larger eggs such as those from Archachatina and Megalobulimus (oblongus)can be fairly tricky, with Archachatina marginata var. ovum of particular note. This seems to be partly because of the need for steady, warm, moist conditions.

If you wish to keep them all, I'd leave them where they are because the parent will usually have chosen the best place. This isn't always the case, you'll sometimes see eggs being laid indiscriminately all over the tank and on top of the substrate. You can put a pint glass or tub over them so they don't get disturbed. As long as you don't handle them much they should be fine. If you wish to keep them out of the parent tank, it is best to scoop them out with the soil they are in. Damp and warm, they can hatch from 1-31 days onwards, dependent on species and how long they have been kept inside the snail before it chose to lay.

As mentioned above, large eggs (10mm+) (Archachatina) are often more temperamental. The less you disturb them the better the chance you have of hatching them. They also favour more moisture and it is known that dryness quickly kills them. It remarked that Archachatina eggs can almost survive in free-standing water[1]. Some people have success moving them, even handling them, but I think it is fair to say that they are much more sensitive, particularly in the early stages. As a rough guide, and obviously dependent on species and temperature, they should hatch from 20 days onwards.

In both cases, even if laid on the surface I would cover them gently with soil to keep them damp.

The viability of the eggs is usually 80-100%, dependent on species and conditions.

Please bear in mind that there are always more eggs in a clutch than you imagine. I estimated my first clutch to be about 40-50 eggs and there was in fact 90!

Care of the Young Snails

Picture courtesy of Beth

Picture courtesy of Beth

Young snails may stay buried for up to a few weeks, while they ingest and survive on the egg albumen and shell. It is important that they are allowed to consume their shells, as research by "Plummer" has shown (in Archachatina marginata) that failure to do so increases the mortality rate and possibly impedes growth rate. Early hatchers often predate on eggs near them so if you wish to move new hatchlings for this reason it's important to move any egg casing that still remains. Bringing to them to the surface early may result in what seems like normal behaviour but they will still probably refuse to eat normal food for at least a few days.

You should take care not to allow places where they may drown or be crushed. I'd recommend avoiding using water dishes, regular spraying will provide enough water. They're definitely not practical to keep with your adult snails. A small Tupperware tub is much better and means you can check on them very easily without trying to find a needle in a haystack. It is best not to handle hatchlings unless absolutely necessary. If you need to move them, place food in the tank and move this when they have climbed on. Another good way is to scoop them and a little soil up with a spoon. Be very careful when cleaning out, it is very easy to miss them when disposing of food. You can spray them to give them a clean if they require it but be sure to drain any excess water.

Once they reach a size of perhaps 1 cm you should be able to handle them with no problems. Obviously, more experienced owners will decide for themselves when is the correct time to handle them.

Young snails should be capable of rasping cuttlefish but there is certainly no harm in crushing some of it and sprinkling over food or even using milk powder as an alternative. Other than these pointers, young snails live in the same way as adults and require the same care.

Population Control

This is a sticky subject for a lot of people but it's important to think about this sensibly if you intend to keep snails. With certain species able to lay 1200+ eggs in one year it is completely impractical to hatch all your eggs. And with most species, eggs are almost guaranteed. So let's deal with the options you have or may have heard:

Keeping snails isolated

This is a common suggestion but I don't think it is a practical solution for a number of reasons. I'd favour the opinion that snails do best with others and most people wouldn't wish to keep one snail, and you may not have the tanks to start splitting them all up. Also, some species of snail can self-fertilise if necessary (click here for more info).Picking snails that are notoriously hard to breed or in high demand

This isn't a bad suggestion, you'll not have any trouble finding homes for the babies. Remember though, that new breeds are in high demand but may not necessarily be difficult to breed. Your first few clutches may fly out the door, but it's likely those new owners will have similar success. Some species can be fertile within a few months, so the day when you'll struggle to re-home them is merely postponed.

Discouraging breeding through environmental conditions

This is a bit like the rhythm method in humans, in that it is likely to be very risky. Most likely you'll end up with unhappy snails and eggs anyway.

Destroying unwanted eggs

The vast majority of snail keepers choose to destroy any unwanted eggs as soon as they are found. The sooner the better because they develop quite quickly, particularly if the snail has retained them for longer than usual.

Destroying the eggs is more humane than hatching 1000s of unwanted babies. Owners of tropical species do this and liken it much to the viability that is realistically found in the wild. A lot of eggs will be eaten, some won't develop and the chance of a baby snail surviving to adulthood is very poor. To destroy eggs you can simply crush, boil or freeze them, the latter the most popular method. Most people check the soil every few days, particularly in hot weather. More often than not snails will lay against the bottom or side of a tank so they are easy to spot.

Some snails hold eggs inside for longer than usual so the eggs can be more developed but in the majority of cases, great conditions in captivity mean they can lay as soon as they are formed. Native snail eggs generally take longer to hatch than tropical ones, 20-40 days, perhaps shorter in hot weather, so destroying them within a day or two of being laid means they are just fluid with no embryo in. Tropical eggs can hatch within a day or two so you have to be ultra vigilant.

I think kids in particular find this process hard to accept. They see eggs as babies before they are formed but I think if it is explained properly, kids can be made to realise that hatching them would be unfair and in fact, in the wild, would cause environmental problems if we simply favoured one species or animal over others.

Options for people who don't think they can destroy eggs

Picking species that lay eggs that develop relatively slowly, perhaps 4-6 weeks gives you ample time to choose to destroy them early, knowing they are just liquid and no embryo has formed.

If you still don't want to do that then I suggest you keep native species only. That way you can release the babies into the wild, or even place the eggs outside and let nature take over as it would have done. The only trouble is if they lay during winter; because we have heating, their cycle tends to change. Outside, for a lot of the year the weather isn't inhospitable for them and they are forced into dormancy. This isn't the case in captivity and can result in eggs being laid at any time. Placing the eggs outside during cold weather would be like putting them in the freezer anyway so you'd have to keep any babies until a favourable season when you see snails out and about. In the case of eggs, only place them outside during warm spells when eggs are likely to be being laid anyway. Avoid non-native species at all costs because destroying eggs is a necessity.

Breeding Information

I am no expert in any field related to this topic, so errors, misguided assumptions or arguments may be prevalent. However, I've tried to make sense of the subject as best I can.

Self-fertilisation

In "Land Snails in the British Isles By Robert Cameron FE (2003), pg. 1, paragraph 3. [ISBN 1 85153 890 9]" it says:

"The Pulmonates are hermaphroditic. Most are outcrossers, exchanging spermatophores, containing spermatozoa at mating. Others self-fertilise, at least some of the time; in some, parts of the male reproductive system may be lost."

Firstly, I can't be sure that by mention of "self-fertilise" it means "fertilising oneself with ones own sperm" or whether it simply means they control the process of choosing when and which sperm to fertilise themselves with. I suspect the former is more likely to be accurate as it is known that snails can store and select sperm and the second sentence, by virtue of it mentioning the receiving of sperm, implies that isn't the case for self-fertilisation, denoted in the succeeding sentence.

Whilst this is talking about British species, obviously all pulmonate snails are closely related and we don't know for sure that Achatinids aren't capable of it, because nowhere is it stated explicitly. Hodasi mentions self-fertilisation for the species Achatina achatina but we don't know if he was simply fooled by their ability to hold sperm for extended periods of time.

Note: We now have what we believe to be a verified case of self-fertilisation of Achatina immaculata which indicates strongly that Achatinid snails can self-fertilise. We're still waiting for more cases to help confirm this beyond all doubt but it certainly seems to be the case.

It is certainly something to think about, when considering keeping snails in general.

Cross-breeding

By crossbreeding I do not mean breeding between two subspecies/variants such as Archachatina marginata var. ovum and Archachatina marginata var. suturalis. Not only do we know this is possible, we have seen many examples of it. By crossbreeding I mean two distinct species, mating and/or having offspring.

This is a tricky topic to deal with, because it is so incredibly complicated. After a number of conflicting opinions on the subject I have come to the following conclusions.

Originally I thought that a species was a definite compatibility boundary in the sense that species that are sexually dissimilar would have infertile offspring, if they managed to have offspring at all, like in the case of Mules and Ligers. If the offspring were fertile then in fact the specimens were either misidentified, or the two species were in fact subspecies of the same species.

However, a recent article on the hybridisation of fish has led me to a different conclusion. Whilst I was looking into hybridisation I came upon the following paper investigating the potential fertility of hybrids between two native British fish, the Roach (Rutilus rutilus) and the Bream (Abramis brama):

"Adult roach, bream and their presumed F1 hybrid from an Anglian Water reservoir were identified on the basis of morphological and meristic characteristics. The hybrid was clearly intermediate. Four hybrid breeding crosses were induced to spawn by hypophysis. A bream x roach cross (female named first) failed to produce fertile eggs, whereas F1 hybrid x roach, roach x F1 hybrid and F1 hybrid x F1 hybrid all produced fry. Fertility (defined as survival of eggs to hatching) was high for the F1 hybrid x roach back-cross (56%) but low for the others (<2%), in comparison to the pure species controls (roach 69%, bream 76%). Progeny from these crosses were reared until anal fin rays could be counted. These counts indicated intermediacy between the parents and back-crossed individuals, and similarity between F1 hybrids and their F2 progeny. 3

Achatina fulica and Achatina iredalei mating.

Achatina fulica and Achatina iredalei mating.Picture Courtesy of a member of the Italian

Yahoo Group: achatina_gasteropodi

Whilst this isn't directly related to snails I think it does tell us that snails are likely to be able to hybridise and produce fertile offspring. Perhaps not in all cases, but in at least some and quite likely a lot. What is different is the delivery method of sperm. In fish, eggs are laid and then sperm is squirted on and over them. It is inevitable then, that sperm from one species can quite easily come into contact with eggs from a different one during spawning. With snails this isn't the case so the question of whether a snail will a) choose to mate in the first place with a member of a different species and b) ultimately choose that particular sperm donor to fertilise the eggs is not yet clear or documented.

Until more documentation on what the current species list stands at and why, it is unlikely any progress will be made into the field of snail hybridisation any time soon. With species and indeed variants of Achatinids living mainly isolated from other species and variants, there doesn't seem to be many natural precedents or examples to refer to or gain knowledge from.

We have certainly seen two different species mating in captivity and I think it is likely we have seen crossbreeds in captivity. The problem is verifying it conclusively. Often the ancestry of the snails isn't clearly known, and conditions are such that it is rarely clear which coupling resulted in fertile eggs. At least self-fertilisation can be ruled out for any offspring that differ noticeably from the parent; whilst self-fertilisation wouldn't produce identical clones I think it is fair to say it would at least be an example of particularly restrictive inbreeding, and should result in offspring very similar to the parent.

In-breeding

Snails certainly do inbreed, and a lot of snails in captivity are the result of inbreeding, particularly well established species such as Achatina fulica. A lot of the time, this doesn't seem to cause any problems, but recently there has been discussion on the possibility that various problems such as bad shell growth and deep retraction disorder may be the result of inbreeding. I'd prefer to keep an open mind on that until there is sufficient evidence to make a judgement. It is certainly less desirable to have inbred offspring because studies in other animals show conclusively that it does inevitably lead to weakened populations. I do think that invertebrates in general are less prone to weakness than other animals, but it's not something to aim for. There are a growing number of people in the hobby community who want to encourage people to swap snails to reduce this. There have also been calls to keep a record of this somehow, so the progeny of snails can be researched; a family tree if you like. This would also fit in with the need to provide locale info to ID snails. If it was recorded from snails first being imported right through to successive generations of offspring, we'd have a much more accurate map of species in captivity. There are of course problems with knowing who are the parents but we could certainly record the line of "mothers".

I have plenty of ideas about how to achieve and implement something like this but there is a lot of work involved so it isn't likely to happen soon I'm afraid. It's certainly been chalked up on the ever-growing list of things that need doing.

Albinism

There have been increases in the number of albino snails being kept in captivity. These are generally albino Archachatina marginata, wild-caught in West Africa. These seem to be stable albino traits, and have risen in numbers due to the belief that dark-fleshed snails are more desirable to consume than white-fleshed snails. (malacologist society)

We're still not sure what or how many genes are responsible for albino fleshed and albino shelled snails. Breeding these Archachatina marginata have produced albino offspring, but there are other example of albino breeding that have produced normal offspring. This suggests that more than one gene is responsible, and as this topic is complicated enough with one, it's not something I have made any real efforts to progress in.

There seems to be a concerted effort by the albino owners to preserve this trait, so as more experience floods in, we may well learn more about it. Unfortunately though albinos amongst normal populations are rare, and would require selective breeding to stabilise.

There are two main types of albinism, albino-shelled and albino-bodied.

Selective Breeding

This is basically the principle behind standardising unusual traits in a species and can range from size, shape, colour, pattern through to albinism. The natural precedent is set in the various subspecies and colour forms we know about. For anyone considering undertaking a selective breeding programme it must be stressed that any successes should be denoted by enclosing the name in quotes, eg. Achatina fulica var. "raspberry swirl" etc. This is to show it isn't recognised as a proper subspecies/variant.

The way to attempt this is to keep desirable snails and re-home the rest, and then through successive selection then breeding, it may be possible to strengthen your desired trait by reducing the genetic variance. For example if only the largest snails of a colony were bred on and on, small ones being removed from the population, the result over time would hopefully be a more stable population of large snails. By that I mean, there are less small ones to remove in successive generations.

There are many problems with this. Firstly, you may be only keeping a handful of snails each time and you are encouraging fast growth and more breeding. You can't choose until the snails are fully grown. A lot of traits don't feature until adulthood. Size is a good example, because growth rate is not indicative of final size. 1. This means you will have hundreds if not thousands of unwanted snails. If you aren't prepared to kill them, you will have to find homes for them. This is less of a problem for native snails because not only can you release unwanted snails, you can also introduce other wild snails that match your profile to inject new blood so-to-speak into the population.

One problem is that when you are lucky enough to get a unique enough mutation to be interesting but it is the only one. Getting a sinistral snail in a normal dextral population is unusual and you are likely only to get one.

It would be an incredibly slow, expensive project requiring a lot of effort. That's not to say that some unusual forms can't be encouraged in a small way. If I was serious about attempting something like this, I would set up a point of contact publicising the attempt, so people can donate or sell you likely candidates. That way you can leave the breeding process to everyone doing it normally anyway.

Mutations

Mutations do occur amongst snails. Technically speaking, all characteristics are mutations but I am talking about some more unusual ones:

Extra eyes

Snails sometimes can have more eye-stalks than two. They seem to do perfectly well with them and they appear to be functional. It has been reported that in the case where an eye-stalk forks into two points, snipping the end off below the split will result in a normal eye being grown as snails can regenerate eye-stalks. Most people, however, simply leave them be.

Courtesy of Helix-Pomatia.de |

Courtesy of Fi |

Scalariform

A deformity in spirally coiled shells in which the whorls are loosely coiled and the spire drawn out. This is sometimes a natural deformity but can be caused artificially by pests or shell breaks, after which the shell grows strangely. Species like Achatina albopicta are known to suffer particularly from this growth problem.

Picture to the right: Scalariform abnormality next to a normal specimen of Cepaea nemoralis

Picture courtesy of Robert Nordsieck

Umbilicate

Having the umbilicus open. This is an abnormality when it occurs in species that don't have a closed umbilicus. It is known to be a natural deformity, but it is reasonable to assume that it could be triggered by artificial growth problems.

Picture to the right: Umbilicate abnormality in a specimen of Achatina fulica

Picture courtesy of Achatinidae.com

Sinistral & Dextral Aberrations

In a population of snails, most specimens coil one way of the other. Coiling to the right is called dextral and to the left, sinistral. This appears to be universally so in most species and is indicative of selective breeding on a a huge scale back at some time on their evolutionary history. It seems that sinistral snails are not able to mate with dextral snails, at least not often and so over time, as one way becomes a minority, that coil bias disappears, leaving and reinforcing the remaining coil bias.

Specimens that are the opposite of their usual coil bias are sometimes referred to as "King Snails". They are a throwback mutation and it would be worth trying to find someone else, with such a specimen to breed from. Unfortunately the mutation is rare enough for you to be extremely lucky to obtain two specimens from a captive, breeding populations. It may be possible to keep two snails, one of each coil bias, together without them breeding. I say may, because in the absence of more compatible partners, added with the fact that their penises are very long, it may just be possible for them to successfully mate. Presumably, the offspring of such a pairing would produce both dextral and sinistral babies, unless the aberration is purely a recessive trait.

For more information on coiling see: Inheritance of direction of coiling in Limnaea